Here—in Salem—on January 3, 1693—the Supreme Judicial Court held its very first sitting. Now, 325 years later, the Court is back in Salem to commemorate its longevity as the oldest appellate court in the Western Hemisphere.

Condensing the SJC’s 325 years into a short talk is, to use Shakespeare’s phrase, like sifting a lifetime through an hourglass.

So I offer this less-than-Shakespearean, but succinct, statement of the Court’s early history: The Supreme Judicial Court was hatched 325 years ago as an Ugly Duckling—an Ugly Duckling that matured into a beautiful Swan. And Essex County played an important role in that admirable metamorphosis.

|

| 1692 Charter Authorized SJC |

The SJC’s story really begins with the Charter of 1629, under which the Colony of Massachusetts Bay was founded. Knowing that the possessor of the Charter also possessed the rights granted therein, John Winthrop essentially stole the charter and took it with him on his voyage to establish the new Colony. Aboard the flagship Arbella, an emboldened Winthrop gave his celebrated “City on a Hill” sermon prophesizing that Massachusetts would be a beacon of freedom and self-government to the world. As many histories confirm, Winthrop’s prediction was prescient—the 1629 Charter created a republican government of “pure democracy.”

But the mother country was not content to leave its upstart offspring free to run its own life. There were decades of continual struggle. The Crown tried unsuccessfully to recapture the Charter, not only by issuing royal commands, but also by sending ships to seize it.

|

| Increase Mather |

After 63 years of struggle, England finally managed to rein in its headstrong settlement by imposing the rigid and restrictive Charter of 1692, causing Increase Mather, the Colony’s emissary in England, to meekly admit that henceforth Massachusetts would be “more Monarchial, and less Democratical.”

History never forgave Mather for not fighting hard enough to keep Massachusetts Bay a free republic. Nearly a century later, John Adams had Mather in mind when he sneered that the “passivity of this Colony in receiving the present charter in lieu of the first, is … the deepest stain on its character. There is less to be said in excuse of it than the witchcraft [trials].”

Thus, the SJC was born an ugly duckling to the disparaged and unwelcome parentage of the 1692 Charter. It is sadly fitting that witchcraft cases were on the docket on its very first day.

As conflict between Colony and Crown inevitably led to Revolution, there were constant reminders that the SJC was not born as a beautiful swan.

It was, after all, a Royal court. Wishing to emulate British customs, Chief Justice Thomas Hutchinson even had judges wear the shoulder-length wigs and scarlet robes worn on the King’s Bench, dress that John Adams derided as “so showy and so shallow, so theatrical and so ecclesiastical.” Ugly ducklings, indeed.

|

| Mural, Massachusetts State House |

Needless to say, the loyalist Court was on the wrong side of nearly every controversy leading up to the Revolution.

Since the turncoat justices personified royal tyranny, it made perfect sense to the colonists that the Colony’s courts be entirely shut down in response to the 1774 Coercive Acts, England’s retribution for the Boston Tea Party. A popular anti-court uprising rolled from the Western counties to every region of the Colony in the summer of 1774. In Great Barrington, 1,500 locals forcibly prevented the royal judges from entering the courthouse. In Worcester, another hostile mob swelled to 5,000. An anti-judge crowd of 4,000 in Plymouth even tried to dig up and place Plymouth Rock in front of the courthouse. The fact that the courthouse was up a hill and the rock was found to weigh “ten tons at least,” according to one historian, unfortunately doomed this spirited symbolic act.

The North Shore was more sober-minded in its response. Essex County allowed judges to sit as long as they agreed to pretend that the Coercive Acts had never been enacted.

Bostonians were not so tolerant. Even with the presence of British troops they still managed to choke the courts with threats to life and limb. “[T]here were a Number of printed Bills stuck up at the Court house,” one eyewitness wrote, “threatening certain death to any and all of the Bar who should presume to attend the Superior Court”—a reference to the SJC’s predecessor, the Superior Court of Judicature.

“Civil government is near its end,” the royal governor, General Gage, declared in September 1774, “the courts of justice are expiring one after another.”

|

| John Adams |

John Adams summed up the dire situation: “Not a Court of Justice has sat Since the Month of September. Not a Debt can be recovered, nor a Trespass rebuffed, nor a Criminal of any Kind brought to Punishment.”

The popular revolt closing the Colony’s courts in the summer of 1774 effectively put an end to Royal government in Massachusetts. It was inevitable that Governor Gage would abandon Boston and any hope of governing.

The Colony was now in a crisis. Adams wrote of the “utter Impossibility of four hundred Thousand People existing long without a Legislature or Courts of Justice.” There were immediate calls to restore the beloved Charter of 1629 and its freedoms of self-government.

But on the advice of the Continental Congress, the Revolutionary leaders chose to keep the hated 1692 Charter in the quixotic, quickly vanishing hope of reconciliation with Britain. This contrivance governed Massachusetts from July 1775 until the adoption of the Massachusetts Constitution in October, 1780.

John Adams was appointed as chief justice during the interregnum. It is at this point, under Adams’s masterful guidance, that the SJC as ugly duckling started to resemble a swan, and Essex County played a critical role in that transformation.

Although he was in Philadelphia, most biographers mischaracterize Adams as an absentee chief justice distracted with his duties at the Continental Congress. Yet, from afar, Adams nevertheless managed to jumpstart SJC sittings. And, through his compulsive correspondence with nearly every influential leader, he also engineered the tense and tumultuous political process to a new Massachusetts constitution—which he eventually drafted.

First things first. Chief Justice Adams wrote a proclamation designed to strengthen public support for the rule of law. Functioning courts are needed, he pleaded, for “peace, virtue, and good order.” The General Court ordered that Adams’s appeal to reason be read at all town meetings and church services throughout the Colony.

Next, looking to sensible Essex County for help, Adams took a first step to resume the SJC’s circuit. On June 18, 1776 in Ipswich, the newly reconstituted SJC held its first sitting since mobs had effectively closed the Colony’s courts two years earlier.

|

| Treadwell's Inn |

Associate Justice William Cushing, who would become Chief Justice and later sit on the US Supreme Court, presided and read Adams’s proclamation. There were no menacing protests as many had feared.

Thus Essex County is not only the site of the SJC’s first sitting as a royal court in 1693, but also of its rebirth in 1776.

There were additional sessions in other counties. In September 1776, the court had its first sitting in Boston in roughly two years. Abigail Adams wrote to reassure her husband: “The people seem to be pleased and gratified at seeing justice returning into its old regular channel again.”

Satisfied that respect for the courts was being restored, Adams resigned as chief justice in 1777 and turned his attention to birthing a suitable new constitution.

Massachusetts’s first attempt at adopting a new constitution was resoundingly rejected by the towns in 1778. Deeply flawed, it had been drafted by the General Court.

Here, again, the North Shore played a central role when 12 of the county’s 21 towns met at Treadwell’s Inn in Ipswich and issued the Essex Result on behalf of the County. It was a masterpiece.

|

| Essex Result |

The widely-circulated Essex Result presented a comprehensive critique of the 1778 Constitution’s failings along with a prescription of the “true principles” that should form a new constitution.

It was so influential that some said that it was the blueprint for the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. John Adams seethed at the suggestion. The Essexmen, he grumbled, “need not be so vain glorious as to arrogate to themselves the honor of being the Founders of the Massachusetts Constitution.”

When it came to the true principles of constitutional government, Adams and the Essex bar agreed on the constitutional essentials: a bill of rights, clear separation of powers, a true bicameral legislature, a governor with veto power and—perhaps most importantly—an independent judiciary.

But who should get the credit? Adams said that the Essex Result should have paid tribute to his seminal pamphlet, Thoughts on Government, which had been widely read by political elites, and even influenced constitution making in other colonies. He had a point, because the first newspaper printing that presented Adams’s Thoughts on Government to the general reading public appeared in the Essex Journal.

|

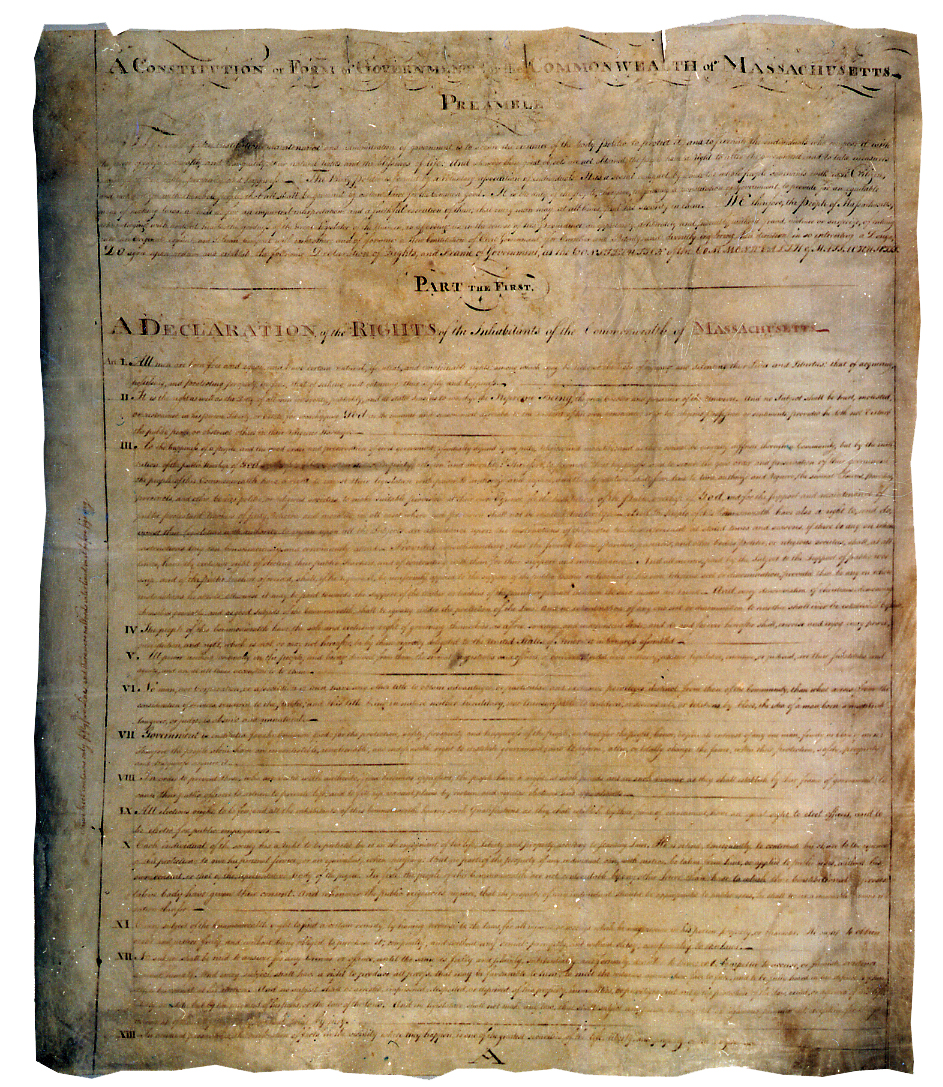

| Massachusetts Constitution |

There’s no doubt that the Essex Result repackaged and popularized some of Adams’s ideas, while advancing its own ideas that made it into the Constitution. As one contemporary wrote, the Essex Result was so widely read that it had “A great Share, and Influence” throughout the colony at the time that towns were voting on the new constitution. Historians also agree that the Essex Result was enormously influential. In his Pulitizer Prize winning book, The Creation of the American Republic, Gordon Wood credited the Essex Result as marking an “extraordinary change” in American constitutional thinking.

The important point is that the bar in Essex County and John Adams were

“on the same page” when it came to the essentials of constitutional government. Evidence of Adams’s respect for the Essex Bar is seen in the fact that he sent his son and future president, John Quincy Adams, to study for the bar with Theophilus Parsons of Newburyport—the man credited with writing the Essex Result and who would later become Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court.

Foremost among the Essex Result’s essential elements for a constitution was a bill of rights.

Of like mind, John Adams placed “A Declaration of Rights” immediately after the Preamble of the Massachusetts Constitution. Article I reads that “all men are born free and equal, and have … the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties.”

Following the Constitution’s ratification in 1780, the Massachusetts courts heard a series of unprecedented slavery cases that put those words to the test.

Chief Justice William Cushing declared slavery unconstitutional, as “effectively abolished as its can be by the granting of rights and privileges [in the Massachusetts Constitution that are] wholly incompatible and repugnant to … [slavery’s]…existence.”

When it abolished slavery by judicial decision 75 years before the Civil War, the Supreme Judicial Court finally spread its wings as a beautiful swan.

One cannot read the ground-breaking slavery decision without thinking of the Court’s 2003 Goodridge opinion providing marriage equality for same sex-couples for the first time in the United States, a constitutional guarantee that is now the law of the land.

In 1785, the SJC embraced the following motto translated from the Magna Carta as its promise to posterity: “We sell justice to no one; we deny justice to no one.”

As it enters its 326th year, may the Supreme Judicial Court continue to advance the rule of law and equal justice for all.

And may the bar on the North Shore continue its tradition of erudition and excellence in service to what the Essex Result called the “true principles of government.”

Robert J. Brink is the Executive Director of the Social Law Library. These keynote remarks were delivered at a special session of the Supreme Judicial Court on January 22, 2018 held in Salem, Massachusetts.